Motobu Choki (1870 – 1944), one of the best karate fighters of his era, and Funakoshi Gichin (1868 – 1957), referred to as “the father of modern karate” by many, had very little in common and very little regard for each other.

While Motobu called Funakoshi’s version of karate hollow, fake, ineffective, and harmful to the world, Funakoshi considered Motobu “a densely illiterate person”.

This post explores the legendary feud between these two great karate masters.

Table of Contents

- About Motobu Choki

- About Funakoshi Gichin

- Motobu vs Funakoshi challenge

- The implication of Motobu’s victory over Funakoshi

- Motobu Choki defeating the foreign boxer

- Motobu Choki’s view on Funakoshi Gichin

- Funakoshi Gichin’s view on Motobu Choki

- Conclusion

About Motobu Choki

Born into a branch of the Ryukyu royal family but neglected because he happened to be the third son (following the tradition of the day that only the first-born son was to be given a proper education), Motobu Choki made karate study the single pursuit of his life.

By the time he moved to Osaka in 1921 at the age of 51, Motobu Choki was already well known in Okinawa as the strongest karate fighter there but he was largely unknown in Japan.

But all that changed overnight when, at the age of 52, Motobu Choki defeated a much bigger and younger Western boxer and became a household name in Japan for his fighting skill.

Following that victory, Motobu was sought after and had the opportunity to teach at several places including Mikage Teacher’s College, Mikage Police Force in Hyogo Prefecture, the Ministry of Railways, and Tokyo University.

Motobu also opened a dojo called Daidokan in Tokyo and later published two books.

When Motobu moved to Tokyo in 1927, Funakoshi had already been there for several years, established a name for himself, and had a large number of students.

Motobu stayed in Japan for 20 years to teach karate. Due to the escalation of the war, he had to close his dojo and returned to Okinawa in 1941. He passed away in 1944 just before the war broke out.

About Funakoshi Gichin

Born a sickly child in a samurai family, Funakoshi Gichin was given a proper upbringing. He was trained in both classical Chinese and Japanese philosophies and teachings.

One of Funakoshi’s school friends happened to be the son of Ankō Asato (1827 – 1906), an Okinawan karate master and so he began training under Asato at the age of 11 and excelled in the art.

Later on, Funakoshi also trained under Ankō Itosu (1831 – 1915), another Okinawan karate master and a pioneer in developing the systematic method of teaching karate techniques and introducing karate to the general public.

Funakoshi began teaching and by the 1910s had already had many students.

In 1912, Funakoshi became the president of the martial art association of Okinawa, the Shobukai.

In 1917, when the Crown Prince of Japan, Hirohito, visited Okinawa, Funakoshi organized a karate demonstration for him.

In late 1921, Funakoshi Gichin (aged 53) and his student, Makoto Gima (aged 26) took part in a demonstration of ancient Japanese martial arts in Tokyo which turned out to be a great success.

Jigoro Kano, the Judo founder, was present and very impressed by this demonstration, so much so that he invited Funakoshi to stay and give another demonstration at the well-known Kodokan (the headquarters of the worldwide judo community founded by Jigoro Kano in 1882).

After that, Funakoshi decided to stay in Tokyo to teach and promote the art of karate.

With the goal of shedding the image of karate as “the art of thugs and the lower class“ and getting it widely accepted by the Japanese, Funakoshi’s style of karate focused on kata training and character building and mostly ignored kumite.

There is a story that three of Funakoshi’s students at the Shichi-Tokudo (a barracks situated in a corner of the palace grounds in Tokyo) decided that kata practice was insufficient and attempted to incorporate free fighting drills using kendo masks and protective clothing.

When Funakoshi heard about these bouts, he considered them belittling to the art of karate and stopped visiting the Shichi-Tokudo altogether.

Subsequently, he also prohibited sports sparring and the first sports competitions did not happen until after Funakoshi’s death in April 1957.

Motobu vs Funakoshi challenge

It appears that the rivalry between Motobu and Funakoshi started when Motobu decided to pay a visit to Funakoshi’s dojo.

Motobu always considered himself a student of karate and it would be natural that when he moved to Tokyo and heard of Funakoshi, he would want to check it out to see if he could learn something from him.

Below is Motobu Choki’s account of that first encounter.

When I came to Tokyo, there was another Okinawan who was teaching karate there quite actively. When in Okinawa, I hadn’t even heard his name.

Upon the guidance of another Okinawan, I went to the place he was teaching youngsters, where he was running his mouth, bragging.

Upon seeing this, I grabbed his hand, took up the position of kake-kumite and said “What will you do?”

He was hesitant, and I thought punching him would be too much, so I threw him with kote-gaeshi at which he fell to the ground with a thud.

He got up, his face red, and said, “Once more” so we took up the position of kake-kumite again. And again, I threw him with kote-gaeshi.

He did not relent and asked for another bout, so he was thrown the same way for the third time.

Kake-kumite is a traditional form of jyu kumite or free sparring practiced in Okinawa but has been largely replaced by the modern free sparring style.

In kake-kumite, opponents begin by crossing their right arms against each other. All techniques are allowed but should be stopped shortly prior to the target to minimize danger.

Other names for this form of sparring are kakete or kakede (hooked hands). There is also a related sparring practice called kake-dameshi (contest of kakede) where people test out their ability within agreed rules under the watch of an observer.

According to Motobu’s account, he initiated the challenge by grabbing Funakoshi’s hand and assuming the kake-kumite position. He then twisted Funakoshi’s wrist and threw him to the ground. This was repeated two more times at Funakoshi’s request.

This must have been a devasting blow to Funakoshi’s ego, especially when it all happened in front of his students.

Konishi Yasuhiro, a student of Funakoshi who later left to train under Motobu said the following about this challenge.

I heard that Motobu met Funakoshi and they talked about how various attacks could be effectively received.

When Motobu asked him to show him a block against a punch, when Funakoshi blocked the technique, Motobu seized his hand and threw him about three and a half meters.

I’m not sure if this is true or not but I do know that since that time, Funakoshi hated Motobu very much, referring to him as an illiterate. Therefore, I was not surprised when Funakoshi’s student hated me for supporting Motobu.

The implication of Motobu’s victory over Funakoshi

We don’t know for sure the exact details of what happened but I think we can establish one thing: there was indeed a challenge between Motobu and Funakoshi in which Motobu won.

This is unsurprising given that Motobu Choki had a lot more practical fighting practice than Funakoshi ever had, if any, and that Motobu Choki had a bigger build and was perhaps a lot stronger.

Losing a challenge against Motobu does not make Gichin Funakoshi any less of a great master but it does say that the effectiveness of Motobu’s karate style surpassed that of Funakoshi.

Dave Lowry wrote in Blackbelt Magazine that challenges were common and competitions were fierce in the 1920s and 1930s and that when Funakoshi began teaching karate, those challenges were numerous and serious.

Here is how the dojo challenge (dojo yaburi) works. The man who issues the challenge must fight the lowest-ranking student in the dojo. If he wins, he’ll be allowed to fight the next-level student in the dojo, and so on. Only after he defeats the most senior student, he is then allowed to challenge the sensei.

However, luckily for Funakoshi, he had two excellent students, Yasuhiro Konishi and Hidenori Otsuka (both became students of Motobu later on) who were eager to face those challengers. They were very successful in defeating those challengers and helped solidify the reputation of karate.

It is very probable that Funakoshi never had to face a challenger before Motobu came along and embarrassed him in front of his students.

There is also a record of another challenge that Motobu initiated in which Funakoshi again failed.

Motobu was accompanied by a strong young fourth dan judoka and, in an attempt to make Funakoshi lose face, he arranged for a test whereby Funakoshi had to escape from the judoka’s grip on his collar and sleeve. “Now”, he said to Funakoshi, “you are so proud of your kata, show me what value they have in this situation”.

Funakoshi accepted the challenge but was unable to break the grip of the judoka and was thrown into the wall of the dojo.

This was probably another attempt by Motobu to prove that Funakoshi’s style of karate with too much focus on karate did not work. It might be due to Motobu’s strong belief that “nothing is more harmful to the world than a martial art that is not effective in actual self-defense” rather than an intention to embarrass or destroy Funakoshi’s reputation.

In this context, it is easy to understand why Funakoshi would hate Motobu so much and refer to him as a “densely illiterate” and that “whenever the name of Motobu was mentioned, Funakoshi’s face contorted“.

Motobu Choki defeating the foreign boxer

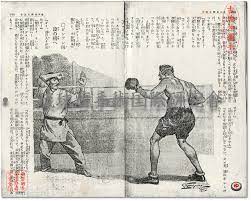

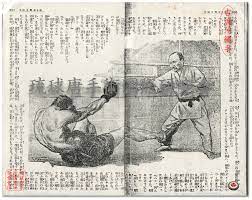

In 1922, Motobu Choki, at the age of 52, soundly defeated a much bigger and younger foreign boxer and became a household name in Japan overnight.

However, when the Japanese magazine Kingu (a major general interest magazine with a circulation of over a million) published an article about this bout in 1925, the illustrations in the magazine clearly showed Funakoshi confronting and defeating the foreign boxer and not Motobu.

Motobu Choki was correctly named as the challenger of the bout and photos of both Motobu Choki and Funakoshi Gichin appeared in the article, so it was hard to understand why the magazine’s artist could confuse between the two.

It is impossible to think that Funakoshi would have had anything to do with this stuff up but it probably further intensified the feud between Motobu and Funakoshi.

Motobu Choki’s son, Motobu Chosei, said that “his father was incensed by this and suspected that it had been done in an effort to give Funakoshi credit for something he had not done“.

Motobu Choki’s view on Funakoshi Gichin

Motobu Choki “referred to Funakoshi’s karate as a Shamisen (3-stringed Okinawan guitar): beautiful on the outside but hollow on the inside“.

Motobu did not mince his words when talking about Funakoshi’s version of karate.

Funakoshi’s karate was fake… he could only copy their [the masters’] elegance by performing the outer portion of what they taught and used that to mislead others into believing he was an expert when he was not…

His demonstrations were simply implausible. This kind of person is good-for-nothing scallywag.

Funakoshi is very good at talking, in fact, his tricky behavior and eloquent explanation easily deceives people. To the naive person, Funakoshi’s demonstration and explanation represents the real art!

Nothing is more harmful to the world than a martial art that is not effective in actual self-defense.

If that stupid person opens a dojo then let him fight with me and I’ll make him go back to Okinawa. This would be a real benefit to the world.

Upon hearing that Funakoshi was granted a 5th dan from the Kodokan, Motobu quipped “if that’s the case then what am I, a 10th or 11th dan?“

Nevertheless, Motobu may have been a little jealous of Funakoshi’s success too and felt it was unfair because he was certain that he was a far better karate fighter than Funakoshi.

Funakoshi Gichin’s view on Motobu Choki

Gichin Funakoshi on the other hand “maintained that Motobu was a densely illiterate person” and “whenever the name of Motobu was mentioned, Funakoshi’s face contorted.”

This is in contrast to one of the precepts that Funakoshi had written that “karate begins and ends with respect”.

Funakoshi certainly didn’t respect Motobu despite his technical ability being far superior to his own and worse, after he lost the fight, he attacked Motobu’s character and called him an “illiterate” and an “irreconcilable enemy”.

Funakoshi, having had a proper education and being trained in classical Chinese and Japanese literature, had a point there given Motobu’s inability to speak Japanese and his relaxed mannerism of an Okinawan.

However, although Motobu could not speak Japanese, discovered writing of Motobu proves that he was not illiterate. He also published two books on karate.

He was home-schooled and was not taught Japanese at a young age and it would have been very difficult for him to learn Japanese as an adult in his fifties. This affected his ability to teach and develop a larger following.

Conclusion

Motobu Choki clearly did not respect Gichin Funakoshi’s version of karate which he viewed as impractical and harmful and I would side with Motobu on this point.

While Funakoshi had made a great contribution to the spreading of the art, his version of karate was a watered-down version of the effective and deadly Okinawan te.

Funakoshi’s focus on kata practice and the omittance of kumite in an effort for it to be accepted by the Japanese resulted in an impractical karate style that would not work well in a real fight (note that the Shotokan style today is very different from and far more effective than what Funashoki taught then).

No one can become a good fighter by practicing kata alone. Each kata is like a volume of combat techniques and one will never know if these techniques work or not if one does not test them out thoroughly in actual combat.

However, there may be an element of jealousy on Motobu’s part. He knew that he had better technical knowledge and better fighting ability but was a lot less successful than Funakoshi.

Personally, I have to admit that I used to have very high regard for Funakoshi Gichin for the contribution he did to spread the art of karate in mainland Japan and the rest of the world.

However, after doing research about Motobu Choki and learning about the feud between him and Funakoshi, I was quite disappointed by Funakoshi’s behavior in this regard.

To put it bluntly, Funakoshi did not walk his talk in some respects.

Despite saying that “the ultimate aim of karate lies not in victory or defeat but in the perfection of the character of its participants” and that the “art of developing the mind is more important than techniques” he himself appeared to be petty-minded after losing against Motobu.

There is nothing wrong with losing against a stronger opponent and one should view it as an opportunity to improve one’s skills but Funakoshi didn’t treat this defeat the way a genuine martial artist should.

When his students left to train with Motobu to widen their karate knowledge, Funakoshi also considered it an act of betrayal, which is unacceptable by both the moral standards of today and then. This is very difficult to understand because Funakoshi himself had studied under many karate masters.

Other posts you might be interested in:

Motobu Choki’s Karate Principles Through Quotes

Motobu Choki’s Fight with a Boxer that Brought Him Fame

Yoshimi Inoue: The Life of a Legendary Karate Instructor

Valuable Karate Lessons From Yoshimi Inoue (Part 1)

Valuable Karate Lessons from Yoshimi Inoue (Part 2)

How to Improve Your Kata Performance: 5 Surprising Tips

How to Generate Explosive Power in Your Karate Punches

References

“My Art and Skill of Karate” by Motobu Choki (1932), translated by Andreas Quast and Motobu Naoki

“Karate – My Art” By Motobu Choki, translated by Patrick and Yuriko McCarthy

Choki Motobu: Through The Myth To the Man

Supreme Master Funakoshi Gichin

Gichin Funakoshi Sensei Informal Biography