Fighting science in Motobu Choki’s time was pretty much non-existent but he was a martial genius and way ahead of his time in many ways. In this article, we will explore how Motobu Choki trained to become what many regarded as the best karate fighter of his time in Okinawa as well as in mainland Japan.

Table of Contents

- Building a strong body

- Mastering a few katas

- Adopting a simple and practical fighting system

- Daily practice and never stop learning

- Conclusion

Building a strong body

Motobu Choki totally understood how important it is to build a strong body in order to become a good fighter. To achieve this goal, his training included hitting the makiwara on a daily basis, stone-lifting, chishi practice, and training both sides of the body.

1. Makiwara

Like many other karate masters of his day, Motobu Choki knew the importance of makiwara practice but his diligence gave him unique and unmatched power.

Makiwara training was the core of traditional Okinawan karate practice for it is essential in achieving the goal of ending a physical confrontation quickly and decisively. Only through thousands of hours of makiwara practice over many years, one can learn proper body mechanics and be able to, when needed, instantaneously generate explosive power that causes a devastating destructive force upon his or her opponent.

Motobu Choki understood this and considered the makiwara “a must equipment for a karate student to exercise his skill“. [1]

According to Shoshin Nagamine (1907-1997), an Okinawan karate master and student of Motobu Choki, Motobu would sometimes sleep in the dojo and if he woke up during the night, he would get up and hit the makiwara instead of going back to sleep. [2]

Some sources say that Motobu would strike the makiwara a thousand times a day. Given that it would take about 20 to 30 minutes to strike that many times, it is highly likely that that was what Motobu actually did. [3]

Motobu Choki had this to say about his own makiwara practice: “When I was young, I made a makiwara on a large tree at my home, and a friend and I struck it. Within a week, the tree had died. It was rather odd.” [4]

With daily makiwara practice since childhood and practical fighting experience, Motobu came to the conclusion that seiken (a traditional knuckle punch where contact is made with the first two knuckles) was not powerful enough in close-quarter fighting and that keikoken (one knuckle punch) or uraken (back fist strike) would be more destructive. [5]

In actual fighting, you must get close to the opponent in order to give him a fatal blow. However, when you get too close to the opponent, you can’t use seiken properly and effectively. In this case, either keikoken or uraken can produce the most vitally destructive power.

Motobu Choki

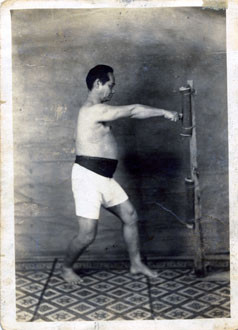

Below is a photo of Motobu Choki striking the makiwara with the keikoken.

And with a lot of practice, Motobu was able to develop incredible power with his keikoken. According to Shoshin Nagamine, “I have seen many people striking the makiwara … but never have I seen anyone reproduce the awesome power generated by Master Motobu. His keikoken was, pardon the play on words, truly shocking.” [6]

Some sources say that Motobu used his favorite keikoken technique to defeat a much younger and bigger foreign boxer in a challenge match at the age of 52.

2. Strength training

While many martial artists today still don’t understand the importance of strength training because they mistakenly think that strength training will bulk them up and slow them down, Motobu knew its importance in building overall body strength and encouraged the use of training tools like ishi (oval-shape stone), chishi (stone lever weight) and sashi (stone hand weight). [7]

In his book, “My Art and Skill of Karate” published in 1932, Motobu said that “these primitive utensils are essential for the practice of karate”.

(i) Ishi (oval-shape stone)

According to Motobu, beginners should lift stones weighing about 42 kg (92 lb) to start with and they should lift it twice a day, every morning and evening. As one’s strength increases gradually, the weight load can increase to around 78 kg (172 lb).

(ii) Chishi (stone lever weight)

The chishi is a dish-shaped stone or iron with a wooden handle inserted in the center. The wooden handle’s length is between 30 and 33 centimeters.

By swinging the chishi in various directions (e.g. swinging to left and right and over the shoulders), it can help improve the strength of your shoulders, arms, and grips.

You can make a chishi at home easily with just a length of solid wood, some ready-mix concrete and a mold (e.g. an ice-cream tub). Remember to add a few nails to the end of the handle before placing it in the wet concrete to improve structural integrity.

(iii) Sashi (stone padlock)

The sashi is shaped like a padlock and made of stone or concrete. It is used to increase the strength of the shoulders, arms, grips, and wrists.

Below is a video of Gima Tetsu Sensei of Jundokan demonstrating how to use the sashi.

It’s not easy to make your own sashi without stonemason skills, but you can use a pair of dumbbells or kettlebells of around 3-5kg each to achieve similar results. To avoid injury, please remember to build up your strength gradually by starting with lower weights and low reps.

4. Developing a balanced body

Lastly, in relation to building a strong fighter body, Motobu Choki stressed the importance of developing a balanced body and that we should devote time and energy to training our weak side.

In his second book “My Art and Skill of Karate”, Motobu Choki recommended that: [8]

During makiwara training, one should start with the left side first because it is usually less powerful than one’s right hand and requires twice the work. So, for example, if one strikes 20 times with the right hand, they must strike 30 times with the left. If one strikes 30 times with the right hand, then they must strike 40 times with the opposite side.

The same principle should apply to all aspects of your karate training whether in practicing your basics or bunkai drills. Make a point of starting any new technique or drill with your weaker side and give it 15-20% more training volume than the dominant side.

An overwhelming majority of us are not ambidextrous and so if we don’t over-train the weak side to compensate, one side of our body will not be as strong as the other. It is obviously better to have two equally strong arms and two equally strong legs than two weak and two strong weapons.

Training both sides of the body and making an effort to develop the weaker side also forces us to use both sides of our brains and boost cognitive functions.

Mastering a few katas

It may be true that Motobu Choki did not know many katas like other masters, but of the few he knew, he thought about them deeply and was able to apply what he learned in those katas in practice.

Like many other things in life, it’s not how much knowledge you accumulate on a particular subject that matters but how much of that you can actually put to practical use.

Motobu may have only known only a few katas but according to Konishi Yasuhiro (1893 – 1983), a student and supporter of Motobu Choki, Motobu thought deeply about every detail of a kata.

For example, in the Naihanchi kata, Motobu taught his students that when performing nami-gaeshi (returning wave foot movement), the foot should be put down lightly instead of a forceful stomp. This didn’t reduce the power of the technique because he once broke an opponent’s leg with this stamping technique. Motobu explained that if the nami-gaeshi was brought down with a big crash, it could compromise one’s balance and defensive posture during the movement. [9]

If you watch the videos below, you will see that in the Shotokan version of the Naihanchi kata (called Tekki Shodan), nami-gaeshi is performed like a forceful stomp.

However, in the Motobu version (second video) performed by Motobu Chosei (Motobu Choki’s second son), nami-gaeshi was performed with a gentle landing of the foot. This is also similar to how it is typically performed in the Wado Ryu style (third video). This similarity is not surprising because Hironori Ōtsuka, the founder of Wado Ryu, studied under Motobu Choki for a period of time.

It’s interesting but when I just think about performing a kata, even when I’m seated, I’ll break a sweat.

Motobu Choki

When teaching his students, Motobu applied the same principle: quality over quantity.

Motobu did not want to teach a large number of kata for the purpose of running the dojo. As a general rule, he only taught Naihanchi kata but would sometimes teach Passai and Seisan if requested. Despite being ridiculed by some that he only knew Naihanchi, he stuck to his principle. [10]

According to Konishi Yasuhiro “Motobu Sensei’s favorite kata was the Naihanchin kata. As a teacher, he knew many katas, but would only teach them once the student had mastered Naihanchin.” [11]

In his second book “My Art and Skill of Karate”, Motobu listed a number of katas but only gave step-by-step instructions to the Naihanchi kata which he believed contained a complete fighting system. He also noted that:

Kata should be taught as close as possible to its use in reality (i.e. actual combat) and not selectively to increase strength (i.e. for physical training purposes).

While Shosin Nagamine was studying under Motobu, they “always took the study of kata very seriously, and spent much time practicing its application and movement“. [12]

Motobu was certainly unhappy when observing changes in how kata was taught in mainland Japan compared to Okinawa. According to Shoshin Nagamine: [13]

He was sad that with the popularity of [karate], there also came great changes. The kata practiced in Tokyo had been carelessly changed, and in some cases had completely disintegrated. In Okinawa during the old days, students spent years meticulously learning a single kata or two. That custom in Tokyo had changed to the pointless but popular practice of accumulating many katas without ever understanding their respective applications. The practice of kata had been reduced to stiff and fixed postures, without tai sabaki (body movement) or ashi sabaki (stepping and sliding.) Kata had become a lifeless practice, Motobu believed.

In short, Motobu didn’t see the point of learning many katas for the sake of learning katas. He may not have known as many katas as other contemporary karate masters, but he knew those few deeply and spent a lot of time analyzing and testing out their applications.

Adopting a simple and practical fighting system

Motobu’s karate is all about efficiency and practicality and it looks pretty simple. Its main characteristics are:

- Adopting a natural stance

- Using the “coupled hands” in actual combat

- Focusing on hand techniques and kicks are used sparingly

- Mastering just one kata

- Practicing a very small number of kumite drills

- Testing out techniques in actual fights.

We will look at each of these features below.

1. Adopting a natural stance

Motobu made it clear that the basic stance is the character-eight stance (Motobu called this hachimoji dachi but also referred to it as naihanchi stance in his book).

This stance is derived from the natural way of human walking and this stance is what you should assume while striking the makiwara, according to Motobu.

In this stance, you will need to keep the width of the feet and the height of the hips as they are in the naihanchi stance, and twist the posture to the left and right. Also, make sure your weight is evenly distributed on both feet. [14]

Motobu explained why his preferred stance was Naihanchi and there were no other fancy and impractical stances in his karate as follows:

There are no stances such as neko-ashi, zenkutsu or kokutsu in my karate. Neko-ashi is a form of “floating foot” which is considered very bad in bujutsu. If one receives a body strike, one will be thrown off balance. Zenkutsu and kokutsu are unnatural and prevent free footwork. The stance in my karate, whether in kata or kumite, is like Naihanchi, with the knees slightly bent, and the footwork is free. When defending or attacking, I tighten the knees and drop the hips, but I do not put my weight on either front or back foot, rather keeping it evenly distributed.

Motobu Choki

If you watch UFC and Karate Combat fighters of today, they all more or less adopt a natural stance and there are no such things as long and deep zenkutsu dachi or floating neko-ashi stance.

Motobu also said the following about the general posture and how it impacts one’s mobility and ability to respond to an opponent in a fight.

When you face an opponent, be sure to assume a posture which is not too wide. Too wide is impractical and leave one with little mobility. Mobility is the foundation of responding effectively. One must move freely, instinctively, and intelligently. Body language is improtant, never telegraph your intentions. Liberate yourself from fixed postures and seek to cultivate unconstrained technique and movement.

Motobu Choki

2. Using the “coupled hands” in actual combat

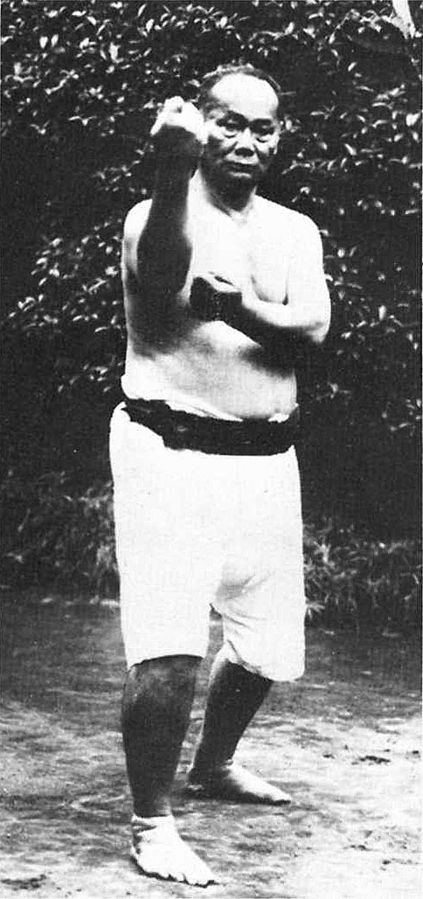

With regard to the positioning of the hands, Motobu believed a position referred to as “coupled hands” or “husband and wife hands” (meoto-de) should be assumed. Below is a photo of Motobu in this hand position.

Motobu’s view was that, with this position, the front hand can both defend and attack and so can the back hand.

In case of actual combat, both hands must always be positioned as … “coupled hands” (meoto-de).

Speaking of how to make use of these two coupled hands, since the front hand fights in the front line, it both attacks and defends. In other words, whether it thrusts, or whether it receives the enemy’s attack, it immediately thrusts at the same time.

The rear hand is continuously employed as a reserve, so when you can’t make it with your front hand, you can still attack and defend with your rear hand.

Motobu Choki

This point of view shows how Motobu was way ahead of his time.

The contemporary view of the time was to place only one hand forward and the other hand was to attach to the side of the torso (also called hikite/pulling hand/chambered hand placed at the hip). In this position, the front hand would be used as the defending hand and the back hand or the reserve hand would be used to attack.

However, Motobu considered this hand position as “a severe mistake” and not effective in actual combat because it would be too late in a real fight. Motobu would often use the front hand to strike and when asked about which hand should be used to attack, he said that “the hand closest to the opponent.” For this reason, Motobu was known to not favor the reverse punch. [15]

In addition to the timing issue, placing the backhand further backward and close to the torso also exposes more of your vital area and makes you more vulnerable to attacks.

3. Focusing on hand techniques

Motobu focused more on hand techniques and was of the view that “kicks are not all that effective in real confrontation“.

For this reason, Motobu was known to have calloused hands from his relentless makiwara training. In addition to his favorite keikoken and tsuki techniques, Motobu also included ura tsuki and empi strikes which are effective in close combat. [16]

However, kicks such as front kicks, side kicks and knee kicks were also included in his practice but they were generally low-level and fired from a close distance. Roundhouse kicks, flying kicks and other fancy kicks introduced from other martial arts were not used by Motobu. [17]

4. Mastering just one kata

Motobu devoted his life to becoming the best fighter he could and he was only interested in learning things that could help him achieve this goal. This also applies to learning kata.

As mentioned above, Motobu didn’t want to learn many katas just for the sake of knowing many katas. He also didn’t want to teach his students many katas for the sake of running a dojo.

Motobu knew that learning many katas wouldn’t help him or his students to become better fighters. Only by learning a few but fully understanding the practical applications of the techniques in the kata and practicing them over and over again, one would be able to use these techniques naturally and instinctively in actual combat.

For a long time, I have also received regular instruction from Matsumura Sensei and the practice of kata always focused on how to place power into kata as well as on the practical use of kata.

That’s true just like that and I have been following his teachings to this day.

Even if your strength is superior to that of other persons and your body is well trained: if you have not fully mastered the practical applications, in a sudden situation, you will be unable to act with speed, and because of this, such a martial art is of no use whatsoever.

Motobu Choki

And Motobu found that Naihanchi kata was enough and that all fighting principles could be found inherent in this short kata.

Motobu’s version of the Naihanchi kata is also slightly different from some versions taught today in three aspects: [18, 19, 20]

- As mentioned above, Motobu’s Naihanchi is characterized by quiet footwork because he believed strong stomping movements are detrimental to one’s defense during the movements

- The Naihanchi stance in Motobu’s kata is higher and narrower compared to the typical wider and deeper kiba dachi stance used in some versions of the kata

- There is no squeezing of the soles of the feet together in Motobu’s Naihanchi stance as per Anko Itosu’s version. Motobu believed this stance would be weaker and make you vulnerable to attacks from behind: “if you try to stand in the character-8-stance … and squeeze the soles of your feet together, and another person just slightly pushes you from behind with the fingertips, you will easily fall over. Thus no matter how much strength is put into this posture, there is no effect whatsoever.”

With regard to the second point, there are some arguments that deeper, wider or longer stances, though impractical, can help build up lower body strength and if you can execute those techniques in those deep stances, you will have no problem doing them in higher and more natural stances.

However, Motobu was a firm believer in all things practical in his karate, if you don’t fight that way, why train that way and that “kata should be taught as close as possible to its use in reality, i.e actual combat, and not selectively to increase strength, i.e. for physical training purposes“.

If we want to become good fighters, perhaps we all need a bit of rethinking about the current karate curriculum. Instead of learning one kata after another for grading purposes and fooling ourselves that we are making progress in our karate, perhaps we should go back to the traditional Okinawan way of training. And perhaps we should stick to just one kata that we like best and practice till we really know it inside out and can actually use it in our sparring.

5. Practicing a very small number of kumite drills

Motobu’s karate is kumite based and he only created a very small number of kumite drills based on his fighting experience.

This again shows how revolutionary was Motobu’s karate at the time.

While other karate masters focused on kihon and kata (e.g. Funakoshi Gichin considered free fighting drills belittling to the art of karate and prohibited sports sparring), kumite drills were the focus of what Motobu practiced and taught. [21]

Motobu Choki included only 12 kumite drills in the first book “Okinawan Kenpo Karate Jutsu” and 6 kumite drills in the second book “My Art and Skill of Karate”. These are all micro-sequences of practical close-quarter fighting techniques. This is because, based on his real-life experience, Motobu knew that street fights usually occur at close range, rather than the long distances that we see in sport karate.

It’s possible that he knew a lot more but perhaps from his 50-odd years of experience training and testing them out in actual fights, these were the most practical and effective to him.

This shows that to be a good fighter, you don’t need to know hundreds of techniques superficially. You just need to know a few techniques but know them really well to the extent that you can actually use them in combat.

A shodan blackbelt in Shotokan is required to know 10 kata and around 40 different kumite sequences in around a five-year period. A Goju Ryu blackbelt will need to learn 5 katas and about 40 kata bunkai and kakie and basic kumite drills in total over the same period of time.

Motobu Choki would have considered it to be a waste of time to learn so many katas and kumite drills, many of which are unlikely to ever be used in real fights.

6. Testing out techniques in actual fights

Perhaps, no karate masters of Motobu’s time had the kind of fighting experience that Motobu had.

Motobu was well known for frequenting the Tsuji Machi (the red light district in Okinawa) to test out his techniques.

According to Motobu himself “I started having real fights at Tsuji when I was young and fought over 100 of them, but I was never hit in the face“. This was probably because he believed “one cannot understand the true meaning of something without putting it into practice.“. If you don’t test out your techniques in real fights, you will never find out what work and what doesn’t and you’ll be flying blind all the time.

Nothing is more harmful to the world than a martial art that is not effective in actual self defense.

Motobu Choki

Fighting science has progressed a lot since Motobu’s time but it is still totally possible today to train in a karate dojo and engage in no actual sparring in months.

You may still enjoy karate for its physical fitness, challenges, and other benefits it brings but if you want to become a good fighter, you’ve got to find opportunities to actually fight.

Daily practice and never stop learning

In the book “My Art and Skill of Karate”, Motobu Choki noted the importance of regular karate practice that “Anyone who has the correct martial spirit … can practice under any circumstances, you have to try to practice without fail, twice a day in the morning and evening, even if it is only in the corner of the room“.

Motobu also never stopped learning in his lifetime. He always considered himself a student of karate and some say that was the reason why he didn’t establish a style of his own or had a large following like other karate masters of his time. [22]

The reason he did not have many students was the fact that he always considered himself a student looking for a teacher. He used to change his techniques and methods from day to day. He had many good ideas but had a hard time explaining them without hurting someone…

He considered himself a student first and would always go from school to school in the hopes of picking up a technique or two…

Even at around the age of 60, Motobu was quoted as saying “I still don’t know the best way to strike the makiwara.”

Conclusion

Some sources say Motobu ran out of things to teach students at his dojo after just six months. This might well be true given Motobu’s “narrow” curriculum of essentially just makiwara training, Naihanchi kata and some kumite drills. Some karate students might get bored quickly with such limited learning materials. However, this limited curriculum was what made Motobu Choki one of the greatest karate fighters ever lived.

If you want to become a good fighter, Motobu Choki’s training approach can offer many valuable insights.

If Motobu were alive today and if you were fortunate enough to get to train with him, it wouldn’t take you long to learn all he’s got to teach. But it requires a total commitment and a lot of daily hard work for you to reach a decent level. It also requires a lot of thinking and searching within to bring out the best fighter in you for no two great fighters are the same.

Copying someone else’s technique can, and will, never produce the same results as meticulous personal study and experience.

Motobu Choki

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Motobu Naoki Sensei (Shihan of Motobu Ryu and grandson of Motobu Choki) for the permission to use Motobu Choki’s photos in this article.

本部直樹先生(本部流師範で本部朝基の孫)に本記事への本部朝基の写真の使用を許可していただき、誠にありがとうございます。

Other posts you might be interested in

Motobu Choki’s Wisdom in “My Art and Skill of Karate”

Motobu Choki’s Karate Principles Through Quotes

Motobu Choki’s Fight with a Boxer that Brought Him Fame

The Legendary Feud Between Motobu Choki and Funakoshi Gichin

“Okinawan Kenpo Karate Jutsu” By Choki Motobu – A Review

References

Tales of Okinawa’s Great Masters (Tuttle Martial Arts) by Shoshin Nagamine

“Okinawan Kenpo Karate Jutsu” By Choki Motobu

“My Art and Skill of Karate” by Motobu Choki (1932), translated by Andreas Quast and Motobu Naoki

“Karate – My Art” By Motobu Choki, translated by Patrick and Yuriko McCarthy

Motobu Choki Sensei – MotobuRyu.org

The Essence of Okinawan Karate-do by Shoshin Nagamine

Choki Motobu: Through The Myth To the Man By Tom Ross

“Funakoshi” – Original document by Richard Kim, translated and modified by Mogens Gallardo

“Master Choki Motobu, ‘A Real Fighter'” By Graham Noble, Journal of Combative Sport, February 2000

“A Meeting With Chosei Motobu” by Graham Noble, Classical Fighting Arts Magazine Issue 1